Patent Infringement – Account of Profits or Damages?

The relative merits of pursuing an Account of Profits or Damages

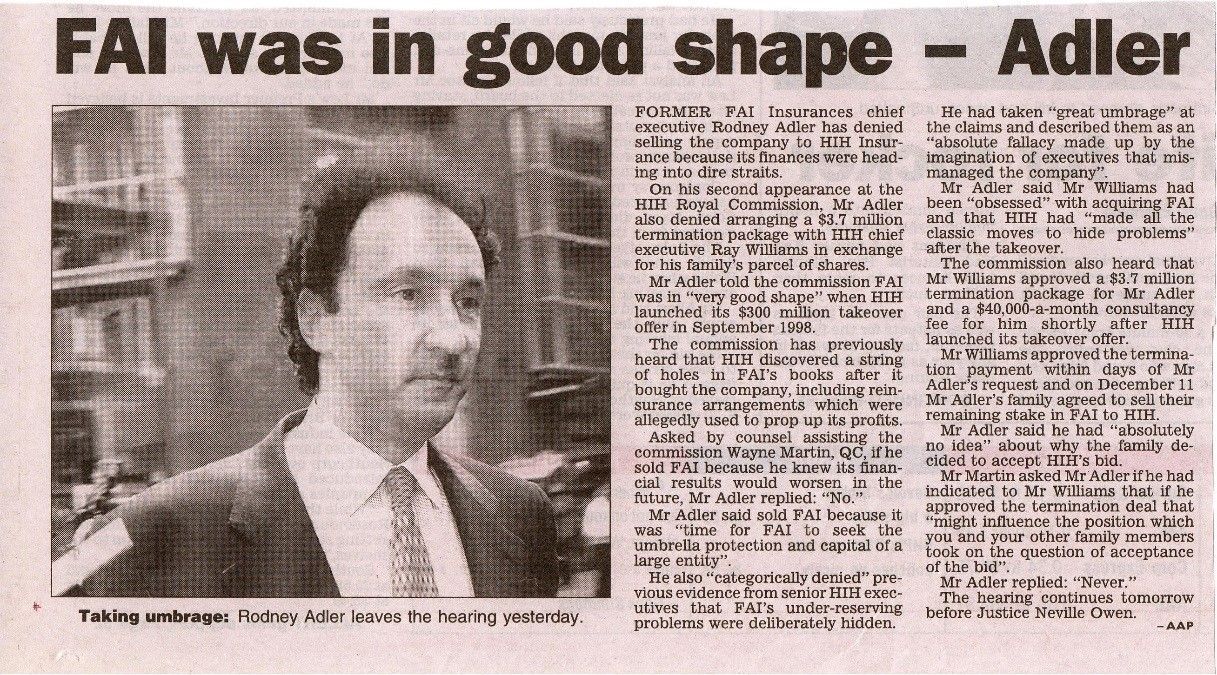

Registering a patent in respect of a product is designed to provide some competitive advantage to the innovator to deter a competitor entering the market and selling a ‘copycat’ product. However, a registered patent does not guarantee competitive advantage as the following scenarios may arise.

Scenario 1 – a competitor does enter the market and sells a copycat product as it is ultimately a matter for the court to determine that a patent is valid in law. It is only when a court determines that a patent is valid that the innovator can claim loss – proceedings could take many years before a judgment is given;

Scenario 2 – an injunction may be sought by the innovator to prevent sales by the new entrant competitor. However, if the patent is subsequently found to be invalid by the court, the competitor will have suffered loss as it could have entered the market and generated profits.

There are two accepted, but alternative, ways to calculate loss as a result of intellectual property (IP) infringement (in this case – a patent) being; an account of profits or damages. The decision as to which method should be chosen is made subsequent to when a court establishes a valid patent (scenario 1 above) or may be made as part of undertaking by the innovator in seeking injunctive relief (scenario 2 above). Irrespective of the scenario, the relative merits of an account of profits and damages needs to be carefully considered. These considerations are both quantitative (and based on very limited financial information) and qualitative (for example, the willingness of a party to disclose potentially commercially sensitive information to support its case).

For the sake of simplicity, the rest of this article will address scenario 1 and assume an ‘Election decision’ needs to be made subsequent to liability being established by the court, that is, infringing sales have been made by a competitor.

Account of profits.

As the name suggests, an account of profits focuses on the profits which have been made by the infringer in respect of the copycat (ie infringing) sales. The objective here is to compensate the plaintiff by taking the profits the infringer has made and giving it back to the rightful owner.

Damages.

Damages is the other option available and focuses on the incremental profits the innovator would have made absent the infringement. The objective here is to compensate the plaintiff by taking into consideration a hypothetical scenario in which the plaintiff would have enjoyed a monopolistic position absent the infringer and the following heads of claim are applicable:

- Loss of profits. This requires an estimation of the market size over the period of infringement period;

- Springboard sales. This requires an estimation of the market size and relative markets share the innovator would have enjoyed after the infringement period;

- Price erosion. This requires an estimation of the reduced price effect as a result of competition over the infringement period;

- Loss of convoyed sales. These are anciliary goods and services which may be sold with the patent protected product eg installation and maintenance profits;

Bearing in mind that the Election Decision as to an account of profits or damages must be made on the basis of limited discovery and prior to any knowledge as to the defendant’s case, the following are some of the relevant considerations:

- An appealing aspect to the account of profits method is that the plaintiff does not need to prove it would have made any of the sales the infringer did actually make. Under damages, the onus is on the plaintiff to prove it would have made the infringing sales. If the plaintiff is not able to prove it would have made any of the infringing sales, then the plaintiff’s claim is limited to a reasonable royalty on the infringer’s sales. Often, the answers lies somewhere in between – that is some, but not all of, the infringer’s sales would have been made by the innovator due to, for example, the innovator and competitor selling to mutually exclusive customers.

- Under an account of profits the plaintiff does not need to disclose potentially commercially sensitive information about its business and its customers as the focus of the investigation will be on the infringer. Pursuing damages comes at a greater non qualitative cost to the innovator in the sense that the level of discovery will be higher and the staff resources needed (and directed away from usual business) will also be higher.

- A damages claim could be substantially higher than an account of profits claim for many reasons, particularly if the innovator believes the claims for price erosion, springboard sales and convoyed sales could be substantial.

- Have all the relevant defendants been included? In some cases, the manufacturer and seller (ie distributor) and may be different entities. For example, the manufacturer may be based overseas and the significant portion of the overall profits in respect of infringing sales may be retained by an overseas entity which is not a party to the proceedings.

- Under an account of profits, the defendant is entitled to absorb overheads in the determination of profits. This can be highly subjective and contentious, particularly where the defendants sell more than just the infringing products as it is obviously in the defendants interest to ‘pull-in’ business overheads to reduce the level of claim.

Conclusion

The above are just some of the considerations which need to be addressed in electing to decide whether to pursue an account of profits or damages in IP infringement matters. Obviously, each matter will be different, for example, in one IP infringement case I was involved in for which damages was pursued, the patent on a dialysis machine was bundled and sold on a ‘price per treatment’ basis. One of the points of contention on this matter was the reliability of the accounting records to allocate the sale price ie price per treatment between specific goods and services sold as part of the treatment. Irrespective of the facts, expert advice should be sought at the earliest opportunity.

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

RECENT ARTICLE:

Acuity Forensic

High-quality forensic accounting and valuation expertise for fair and sensible financial resolutions.

All Rights Reserved | Acuity Forensic ABN: 68 612 783 712

Liability Limited by a scheme approved by the Professional Standards Legislation