Goodwill Hunting

This article analyses the High Court of Australia’s decision in Commissioner of State Revenue v Placer Dome Inc (now an amalgamated entity named Barrick Gold Corporation) [2018] HCA 59 which addresses ‘goodwill’ from the perspective of a valuation professional and forensic accountant giving expert evidence in Australian courts.

On 5 December 2018, the High Court of Australia issued its decision in Commissioner of State Revenue v Placer Dome Inc (now an amalgamated entity named Barrick Gold Corporation) [2018] HCA 59 (“Placer Dome”). The Placer Dome decision required the High Court of Australia to revisit its definition of ‘goodwill’ based on a decision it reached 20 years earlier in Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (B19-1997) [1998] HCA 42 (“Murry”) being a decision it described as ‘watershed’ in relation to the nature, source and value of goodwill. The Murry and Placer Dome decisions expounded on the legal meaning of goodwill and confirmed that it is not the same as what accountants refer to as goodwill. The High Court of Australia in the Placer Dome decision referred to consistency between economic goodwill and legal goodwill, with the former being discussed by economists in the context of a ‘reciprocity’ between seller and buyer which has ‘custom’ at its heart. Whereas accountants typically view goodwill as a ‘residual’ amount (as reflected in accounting standards they are bound by) and therefore an accountant’s understanding and calculation of goodwill is deficient for the purposes of its objective ascertainment at law.

Kiefel CJ, Bell J, Gageler J, Nettle J and Gordon J presided in the Placer Dome case and issued Orders which included:

- the appeal by the Commissioner of State Revenue (in Western Australia) (“Commissioner”) be allowed; and

- the Order of the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia made on 11 September 2017 be set aside.

The Orders effectively upheld an assessment by the Commissioner[1] that Placer Dome Inc (“Placer”) was a ‘land rich company’ under Division 3B of Pt IIIBA of the Stamp Act 1921 (WA) (“Stamp Act”) and that Barrick Gold Corporation Inc (“Barrick”) was liable to pay ad valorem duty of AUD$54.852 million in respect of its on-market share acquisition of Placer which lead to a controlling ownership interest on 4 February 2006. The duty was payable on the value of land Placer owned in Western Australia.

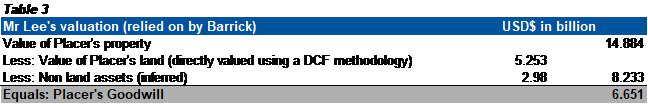

A key issue the High Court of Australia had to consider was whether the property of Placer, at the date of acquisition by Barrick, included goodwill with a value of USD$6.506 billion, being the amount allocated to goodwill in Barrick’s financial statements. A unanimous decision was reached that Placer had no material property comprising of goodwill.

The High Court of Australia’s decision on Placer’s lack of goodwill was reached within a specific legal and factual context. I have sought to condense and summarise the High Court’s reasoning[2] below, focusing my attention to matters of relevance to forensic accountants and valuation professionals who opine on ‘goodwill’ and allocation of other asset values as well as those matters of relevance to tax advisers who rely on valuation advice when giving tax advice to clients in connection with a potential tax-related dispute and tax-related litigation.

What was the legal context for the Placer Dome decision?

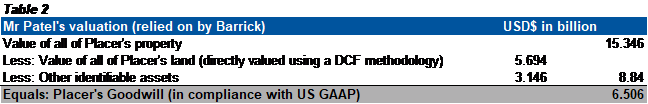

The legal context for the High Court of Australia was to consider valuations applied for a specific statutory test in the Stamp Act drafted for the purpose of government revenue raising[3]. The valuations and statutory test the High Court of Australia had to consider is illustrated in Table 1 below.

Mr Edward Lee, managing director of Duff & Phelps LLC, a valuation firm based in San Francisco, California was also engaged by Barrick (in 2007) to estimate the fair market value of certain assets acquired by Barrick in the course of its acquisition of Placer. Mr Lee’s evidence took the form of the advice which he gave at that time, and a later report in which he responded to the valuations performed by experts engaged by the Commissioner. Mr Lee’s evidence included an opinion on goodwill value, shown in Table 3 below, which was materially similar Mr Patel’s opinion, shown in Table 2 above.

The Commissioner’s valuation evidence

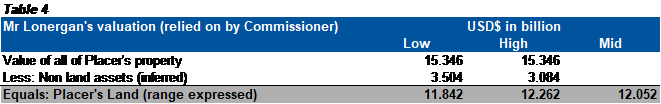

Mr Wayne Lonergan, director of Lonergan Edwards & Associates Pty Ltd, a valuation firm based in Sydney was engaged by the Commissioner to opine on the value of land held by Placer at the time of the acquisition. As shown in Table 4 below, Mr Lonergan arrived at a range for the value of all of land held by Placer.

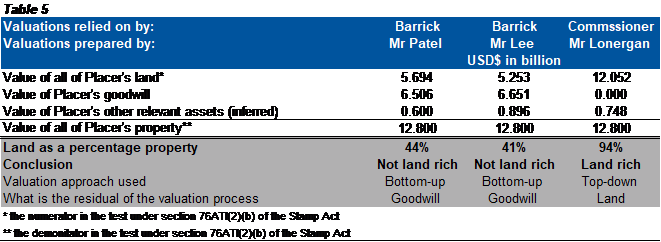

A summary of the competing valuation evidence considered by the High Court can be summarised in Table 5 below.

All valuation experts:

- used the discounted cash flow (“DCF”) method to value all the property of Placer;

- adopted life-of-mine models prepared by Placer in 2005 as part of the DCF method; and

- were likely in agreement over the discount rates for use in the DCF method.

The major differences between the experts related to:

- the appropriate valuation approach to determine the value of land, i.e. whether a ‘top-down’ approach or ‘bottom-up’ approach was appropriate for the statutory valuation purpose; and

- the long-term gold prices used in the DCF method. Messrs Patel and Lee used management and industry consensus forecasts of gold prices at the time of acquisition whereas Mr Lonergan used gold futures contracts at the time of acquisition. The High Court of Australia noted that the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia considered that Mr Lonergan had erred in the use of gold futures prices and therefore Mr Lonergan’s valuation must be considered an unreliable guide to the value of the statutory numerator.

The Commissioner contended that a ‘top down’ valuation approach should be adopted which starts with the value of the total property, before subtracting the value of assets which are not land, in order to produce a residual value which is then attributed to land. In adopting this approach, the Commissioner contended that immediately before Placer’s acquisition by Barrick, Placer had no material property comprising goodwill with the inevitable result that the value of Placer’s land exceeded the 60 per cent threshold resulting in Placer being a ‘land-rich’ company as reflected in Table 5 above.

Barrick disagreed with the Commissioner’s valuation methodology and contended that Placer’s land should be valued directly, using a DCF methodology, and that the resulting valuation of Placer’s land was less than the 60 per cent threshold resulting in Placer not being a ‘land-rich’ company as reflected in Table 5 above. The application of a DCF methodology to value the land can be called a ‘bottom-up’ approach when contrasted with the ‘top-down’ approach relied on by the Commissioner to value the land as a residual. Barrick contended that the DCF calculation directed to valuing each mining tenement according to its best potential use was the standard, and not an inappropriate methodology and that the residual accounting amount – the gap of $6 billion – was attributable to and equal to the value of Placer’s legal goodwill. Barrick identified seven “sources” for Placer’s goodwill being:

- Placer’s personnel, who were said to have proven capacity to develop and expand the business (“Personnel“);

- the technical capacity of the personnel (“Technical Capability“);

- Placer’s innovative mining techniques, which were said to have enabled Placer to extract lower-grade ores, giving it a competitive advantage over other miners (“Techniques“);

- the strong and experienced project group and mine managers (“Management“);

- the size, structures and systems that enabled Placer to harvest efficiencies and economies of scale (“Systems“);

- the synergies (“Synergies“); and

- the going concern value comprising “the value of all the rights and privileges to conduct Placer’s business” (“Going Concern Value”).

In relation to Barrack’s arguments regarding the “sources” of Placer’s goodwill, the High Court of Australia summarised:

“…none of these matters taken individually or collectively is of that character. Some of the “sources” are expressly excluded from the statutory valuation exercise. For some of the “sources”, there is no evidential basis that they in fact exist. And none of the “sources” could generate goodwill of any material value because Barrick could not and did not establish that any of the “sources” could generate or add value (or earnings) by attracting custom to Placer’s business.” [111]

The High Court of Australia’s comprehensive reasoning, based on the factual context, as to why each of items (1) to (6) above was not considered a source of Placer’s goodwill is set out in paragraphs 113 to 138 of the judgment and the comprehensive reasoning as to why item 7 above, based on the factual context, was not considered a source of Placer’s goodwill is set out in paragraphs 96 to 108 of the judgment.

Barrick further contended that even if a ‘top down’ approach were adopted, the result would not be different because, immediately before the acquisition, Placer owned property being goodwill with a value of $6.506 billion. The High Court of Australia considered the difficulty for Barrick was that the DCF methodology of valuing the land assets, as applied by its experts, yielded a large gap between the valuation of Placer’s land assets and the purchase price paid. That gap necessarily raised a question about the reliability of the DCF valuations and, in turn, a question about the content of the $6.506 billion allocated to goodwill in Barrick’s accounts. The High Court of Australia considered Placer lacked goodwill at the time of the acquisition by Barrick particularly noting that Placer’s only product was gold – an undifferentiated product which it sold into a world market at a world price.

High Court of Australia’s findings on goodwill – take-away points for valuation professionals

The High Court of Australia made the following key findings on the nature, source and value of goodwill for legal purposes:

- Goodwill for legal purposes is property because “it is the legal right or privilege to conduct a business in substantially the same manner and by substantially the same means that attracted custom to it”, being a “right or privilege that is inseparable from the conduct of the business”[6]

- Goodwill for legal purposes extends to those sources which generate or add value (or earnings) to the business by attracting custom, whether that be from the use of identifiable assets, locations, people, efficiencies, systems, processes or techniques of the business, or from some other identifiable source. Those sources of goodwill for legal purposes have a unified purpose and result – to generate or add value (or earnings) to the business by attracting custom[7]

- Goodwill for legal purposes is different from, and is not to be confused with, the “going value” or the going concern value of a business. Goodwill represents a pre-existing relationship arising from a continuous course of business – to which the “attractive force which brings in custom” is central. Without an established business, there is no goodwill because there is no custom. A collection of assets has no custom[8].

- Goodwill for accounting purposes is essentially subjective, reflecting the excess that a purchaser is willing to pay for a business or the discount a seller is willing to accept for the same. In this sense, it is essentially a balancing item. However, as a matter of law, the existence or otherwise of goodwill is objectively ascertained. By way of contrast, courts define, and identify, goodwill in differing factual and legal contexts. The definition in one context is more often than not inappropriate in another context. As the majority said in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry, “the nature of goodwill as property may be the focus of the legal inquiry“, “the value of the goodwill of a business may be the focus of the inquiry“, or “identifying the sources or elements of goodwill may be the focus of the inquiry“. That list is not exhaustive. Of particular significance in seeking to define goodwill as a legal term has been the importance of the varying statutory contexts in which the legal question has arisen. The factual and legal context for the Placer Dome decision on Placer’s lack of goodwill is both particular and specific.

While the Placer Dome case specifically related to ‘land-rich company’ provisions in the Stamp Act involving a gold mining company, it has relevance in ‘land-rich company’ provisions in other state base statutes for revenue raising and also in relation to Division 855 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) in relation to CGT that might be payable by foreign resident entities in relation to taxable Australian real property, particularly if it involves a mining company. The goodwill principles in the Placer Dome decision could also potentially apply in other contentious tax matters relying on valuations based on purchase price allocations and therefore any residual goodwill value should be cross-checked against the legal meaning of goodwill.

It is always fascinating delving into what the High Court says about goodwill.

[1] The State Administrative Tribunal in Western Australia originally upheld the Commissioner’s assessment following Barrick’s original objection [2015] WASAT 141 (11 December 2015), which then lead to Barrick appealing to the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of Western Australia, which found in favour of Barrick [2017] WASCA 165 (11 September 2017).

[2] The reasoning of Kiefel CJ, Bell J, Nettle J and Gordon J are set out in pages 1 to 45 and the reasoning of Gageler J is set out in pages 46 to 64 of the Placer Dome decision.

[3] The Placer Dome decision uses the words “statutory valuation exercise”.

[4] The price Barrick paid to acquire Placer (grossed up for liabilities) was USD$15.346 billion. The exclusion relating to the quantum of mining information is inferred to be

[5] In Australia, there are similar accounting standards to US GAAP in relation to requirements for fair values being allocated to identifiable assets on acquisition of legal entities (i.e. AASB 3 – Business Combinations) and also when accounting for goodwill (i.e. AASB 138 – Intangible Assets). Therefore the compliance requirement for Barrick under US GAAP is not considered unique compared to a hypothetical situation of Barrick having to comply with Australian accounting standards.

[6] Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605 at 615 [23].

[7] Commissioner of State Revenue v Placer Dome Inc [2018] HCA 59 at 29 [91].

[8] Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry (1998) 193 CLR 605 at 627 [60].

Leave a Comment:

SEARCH ARTICLE:

SHARE POST:

RECENT ARTICLE: